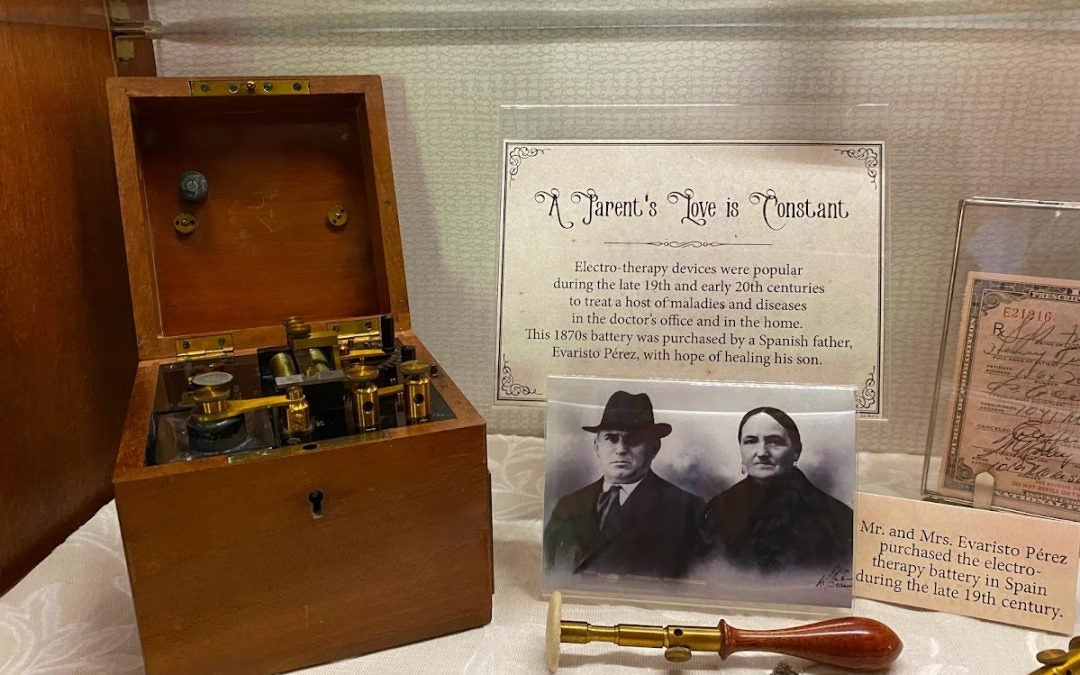

When a visitor walks into the Country Doctor Museum with a box, it usually means they have something to discuss, perhaps a potential donation or questions about something they found. Gary Ambert, a retired Spanish-language professor and ham-radio aficionado, recently brought in such a container. He explained his daughter living in Spain sent him a birthday gift, a little box she thought was an early teletype machine. The small wooden box has little switches and relays on the top with an old glass bottle tucked down into the box. A side drawer opens to reveal a pile of parts and pieces.

As Gary spoke of morse code and radio history, in my mind I could hear the TikTok anthem, “Oh no, oh no, oh no, no, no, no.” I recognized his box as an electrotherapy battery, only his appeared much earlier than examples in the museum’s collection. Gary had also come to a similar conclusion after conducting a Google image search and stopped by the museum for confirmation. To determine an approximate date for the object, we compared it illustrations in a 1925 physician supply trade catalog, but this battery appeared older with its glass bottle which held conductive fluids to create voltage. After additional research, my best guess is that it dates to the 1870-1880s.

Electro-therapy devices were popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to treat a host of diseases and maladies in the doctor’s office and in the home. As more analgesic medicines became available in the 20th century, electro-therapy machines were dismissed as quackery although the benefits of electrical treatments experienced a resurgence of interest later in the 20th century.

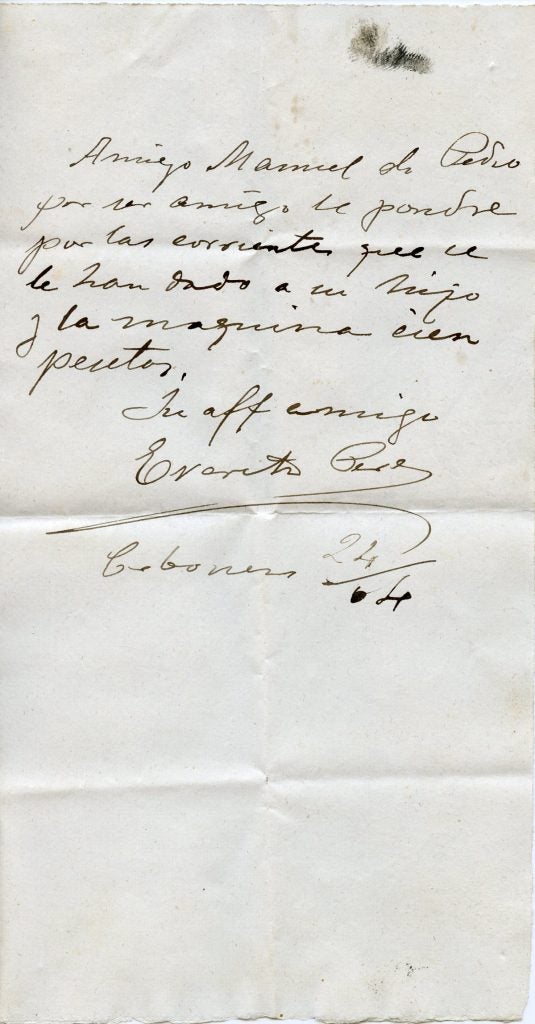

While we examined the battery box, Gary found a folded scrap of paper at the bottom of the drawer. Written in Spanish, the handwriting was difficult to discern but it was addressed to “Manuel de Pedro” and signed, “Evaristo Pérez.” Before Gary left, I scanned a copy of the little note with a thought to send it to one of my best friends, Coralee, a placement coordinator for an international student exchange organization. She graciously sent the scan to Clara, a student from Spain who stayed with Coralee’s family a few years ago. Clara and her mom deciphered the handwriting:

Amigo Manuel de Pedro

Por ser amigo le ponder

Por las Corrientes que se le han dado a su hijo

Y la maquina cien persetas,

Tu aft amigo

Evaristo Pérez

After consulting with our friends around the world, we believe Evaristo Pérez offered to pay 100 pesetas (old Spanish money) to his friend, Manuel de Pedro, for the machine and treatment for his son. Gary’s daughter is friends with a descendent of the Pérez family who tells us that Evaristo’s son died as a child.

Although the medical battery could not help his son cheat death, Evaristo’s note reveals a commonality shared throughout the world and across time: the strength of a parent’s love for their child is constant (just like the battery’s current!) The Pérez’s love and concern perhaps caused them to reach out and try a new medical therapy to help care for their son. The discovery of this personal story makes the interpretation of medical history meaningful to our museum guests. I love how the museum can piece together a historic mystery with clues from a 150-year-old object and connect people in different places and times.